Youth Crew Tours the Middle Rio Fernando Watershed

We started the morning with Vincente and Joe Fernandez, brothers and Mayordomo and Commissioner of the Acequia del Sur del Cañon here in Taos. This particular acequia claims a “priority date” of 1796 and currently has about 300 parciantes – or partners that share the water.

“We survive as a community. We’ve got to share the water – especially in years like this. We sink or swim as a community,” he said standing on the splitter box where river water is diverted to the Acequia del Norte del Cañon and to the Acequia del Sur del Cañon and Randall Reservoir.

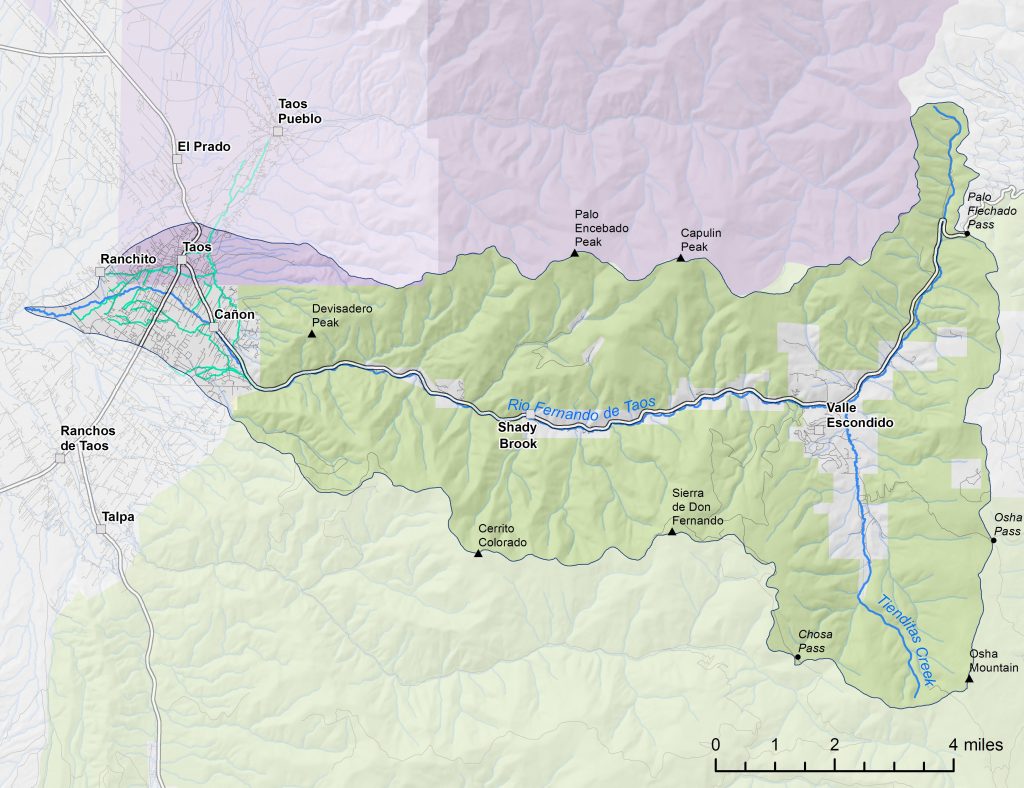

It was a hot Tuesday morning. Another day of drought. As part of our Youth Conservation Corps program we have arranged a range of fieldtrips/tours for the 18 young people doing the hard work to revitalize the Vigil y Romo Acequia and the wetlands at Rio Fernando Park. These tours are designed to give our crews context for their work. On this particular day we toured the middle to lower reaches of the Rio Fernando watershed from the mouth of Taos Canyon to the confluence of the Rio Fernando and the Rio Pueblo de Taos. Along with the YCC crew from the land trust we were fortunate enough to be joined by Taos Town Councilor Fritz Hahn who is both the mayordomo of the Vigil y Romo ditch and a tireless advocate for the protection and revitalization of the acequias and Mark Henderson archaeologist and regional acequia expert.

The Cañon compuerta or presa was a good first stop. Presa literally translates from Spanish as “dam”. This is where the water is redirected from the river into the irrigation ditches. The compuertas are the head gates, but we see those two terms used interchangeably.

“Environmental groups are the ones here fighting for the community,” Vincente said, pointing out that coalitions with community and environmental organizations are helping parciantes to keep his acequia alive.

There are seven acequias that come off the Rio Fernando watershed, watering hundreds of acres of farmland in Taos Valley. This is kind of astounding considering the size of the river. When the ditch was established there was already an awareness that the river was overly appropriated – that there were more farmers with crops needing the river water than the river had water. That continues to be true today – especially in drought years like this one. The result is that some stretches of the Rio Fernando are nothing but dusty ditches, but this might have been true before diversions were established because of natural climactic variations in the watershed.

The biggest issue facing the acequias is non-use, says Fernandez. Hundreds of once-cultivated acres throughout the Taos Valley now lie fallow, threatening the water rights of parciantes who cannot show that they are using the water “beneficially” as required by law.

Being mayordomo, or ditch boss, is about communication. Fernandez explained that much of his job simply involves talking to people, keeping good relations up and keeping people informed on any changes facing the system.

The Fernandez brothers then guided our group downstream to the Randall Reservoir. Constructed in 1903 this large reservoir holds water both for irrigation and fire suppression. This year,

however, it is nearly empty. From the rim of the dam Vincente pointed out hundreds of acres that lie fallow. “Those were once all orchards all watered from here. The danger is that unused water rights can be taken away. That’s not good for Taos,” he said. “We need to keep the water on the land.

Later in the morning we caught up with Bobby Jaramillo, Mayordomo of Acequia Madre del Rio Pueblo de Taos. Jaramillo took us out to the compuerta for his acequia, which comes off the Rio Pueblo de Taos.

The diversion for the Acequia Madre del Rio Pueblo de Taos is on Taos Pueblo land. Out of respect for our Pueblo neighbors we left our cameras behind when we set out to visit the compuerta. Taos Pueblo manages much of its land for wildlife and wilderness values. This is also true of the river where they keep a large amount of water in the river all through the growing season so that fish, birds and the whole riparian ecosystem can continue to thrive. The diversion from the Rio Pueblo is carefully designed to feed both the acequia and the river. This acequia dates to 1797.

Last year there was enough water in the Rio Pueblo that both the river and the acequia got all they needed. That isn’t true this year. By longstanding agreement between the Pueblo and the acequia, Jaramillo can only take water out Friday night to Monday morning but this year there is not even enough water to soak the ditch to the first parciante. All sections of the acequias fed from the Acequia Madre del Rio Pueblo are all dried up this year.

Even though his acequia has nearly 400 parciantes, Jaramillo faces problems getting the ditches properly cleaned and cared for. He simply can’t find enough people-power to get it all done. Last year only two of the parciantes showed up to help so he had to hire a number of workers. But it still wasn’t enough. A proposal to get volunteers to come out and help clean the ditch has proven controversial but Jaramillo is pushing for a volunteer program again for next year.

Councilor Fritz Hahn pointed out that with the way the climate is changing the runoff from the snowpack is not only bringing less water into the Taos-area rivers but that the melt is happening earlier. Traditionally the acequia work happens in late March or April. This year much of the snow had already melted by that time. “We’ve got to adapt,” says Hahn. “We need to start cleaning the ditches in February so that we’re ready for earlier spring runoffs.

At Los Pandos, closer to the center of Taos, the Rio Fernando is totally dry. The atarque, a wooden structure used to move water into diversion channel (similar to a compuerta or presa but much simpler) needs to be rebuilt and is at risk of failing once water starts flowing again. Historically, all the acequias throughout the valley were connected by ditches and rivers creating a vast network of waterways that essentially turned the land into a giant sponge. Unfortunately many of those connections have been lost.

The final stop on our day-long tour of the middle and lower reaches of the Rio Fernando Watershed was the Taos Sewage Treatment plant. This is one of the more advanced systems around – especially for a town our size. Processing millions of gallons of waste water a day from both the town and county sewers and pumped septic tanks from the region, the system (run by seven employees at a cost of about $1.1 million a year) removes heavy metals, pharmaceuticals and pathogens.

The Taos sewage treatment plant supplies water to the golf course, water trucks keeping dust down in construction areas and still returns over a million gallons a day to the Rio Pueblo below the confluence with the Rio Fernando.

Filter membranes hang in an aeration basin, which maintains oxygen levels to support waste-eating bacteria. When wastewater is cycled through other membranes continually removing solids from the wastewater. At the end of the process (and working closely with the New Mexico Game and Fish Department) they filter and disinfect the effluent before it is released from the plant. It runs via an arroyo into the Rio Pueblo de Taos just above the confluence with the Rio Grande. The town gets credit for return flow from the Bureau of Reclamation, which oversees the supplies of and demands for surface water in the western United States.

The removed solids, on the other hand, are processed and cleaned and eventually go to landfill to help decomposition. “Our system produces the best final product in the state,” said Gene Salazar the head of the plant. And it appears true. The end product didn’t smell any different from potting soil.

Next week will are off to the upper section of the Rio Fernando watershed. In the meantime the YCC crew is making quick work of the acequia cleanup at Rio Fernando Park.

If you’d like to see more pictures from this tour be sure to check out our Facebook page and our Instagram account.